9. Some generalised parser generators¶

Non-deterministic parsing algorithms were used by some of the first compilers [1], but the cost of these techniques was high. As a result efficient deterministic parsing algorithms, such as Knuth’s LR algorithm, were developed. Although these techniques only parsed a subset of the unambiguous context-free grammars and were relatively difficult to implement, they marked a major shift in the way programming languages were developed; language developers began sacrificing the power of expressiveness for parsing efficiency.

Unfortunately languages with structures that are difficult to generate deterministic parsers for will always exist. One such example is C++, that is mostly deterministic, but includes some problematic structures inherited from C. Stroustrup was convinced to use the LALR(1) parser generator, Yacc, to build a parser for C++, but this proved to be a “bad mistake”, forcing him to do a lot of “lexical trickery” to overcome the shortcomings of the deterministic parsing technique [13]. Others opted to write C++ parsers by hand instead, but this often resulted in large programs that were difficult to understand. For example, the front end of Edison Design Group’s C++ compiler has 404,000 lines of code [15].

The result of such problems has seen the development of tools like ANTLR, PRECCx, JavaCC and BtYacc that extend the deterministic algorithms with the use of extra lookahead and backtracking to parse a larger class of grammars. Although it is well known that these approaches can lead to exponential asymptotic time complexities, it is argued that this worst case behaviour is rarely triggered in practice. Unfortunately certain applications like software renovation and reverse engineering often require even more powerful parsing techniques.

Programming languages like Cobol and Fortran were designed before the focus of language designers had shifted to the deterministic parsing techniques. Maintaining this ‘legacy’ code has become extremely difficult and considerable effort is spenton transforming it into a more manageable format. The enormous amount of code that needs to be modified and the repeatedly changing specifications prohibit a manual implementation of such tools. As a result more and more tools like Bison and the Asf+Sdf Meta Environment are implementing fully generalised parsing algorithms.

Another example of the application of generalised parsing techniques can be seen in the development of new programming languages. Microsoft Research utilised a GLR parser during the development of C# to carry out a variety of experiments with a “wide range of language-level features that require new syntax and semantics.” [15].

In this chapter we discuss several tools that extend the recursive descent or standard LR parsing techniques. As the topic of this thesis is GLR parsing we are primarily interested in tools that are extensions of the LR technique. However, we also consider some of the most popular tools that use backtracking to extend recursive descent to non-LL(1) grammars.

9.1 ANTLR¶

A straightforward approach to parse non-LL(1) grammars is to try every alternate until one succeeds. As long as the grammar does not contain left recursion then this approach will find a derivation if one exists. However, the problem is that such a naive approach can result in exponential searching costs. Thus the focus of tools that adopt this approach is to try to limit the searching performed. ANTLR (ANother Tool for Language Recognition, formally PCCTS) is a popular parser generator that extends the standard LL technique to parse non-LL(1) grammars with the use of limited backtracking and lookahead [10]. It uses semantic and syntactic predicates that, in particular, allow the user to define which of several successful substring matches should be chosen to continue the parse with.

Semantic predicates, of which there are two: validating, that throw an exception if their conditions fail and disambiguating which try to resolve ambiguities, are declarations that must be met for parsing to continue. Syntactic predicates on the other hand are used to resolve local ambiguity through extended lookahead. Syntactic predicates are essentially a form of backtracking used when non-determinism is encountered during a parse. Semantic actions are not performed until the syntactic predicate has been evaluated. If no syntactic predicates are defined then the parser reverts to using a first-match backtracking technique.

ANTLR generates an LL parser and as a result it cannot handle left recursive grammars. Although left recursion removal is possible [1], the transformation changes the structure and hence potentially the associated semantics of the grammar.

Another top-down parser generator that utilises potentially unlimited lookahead and backtracking is PRECCx (PREttier Compiler-Compiler).

9.2 PRECCx¶

PRECCx (PREttier Compiler-Compiler (eXtended)) is an LL parser generator that uses a longest match strategy to resolve non-determinism; ideally the rule that matches the largest substring is chosen to continue the parse. In practice, to ensure longest match selection PRECCx relies on the grammar’s rules being ordered so that the longest match is encountered first. However, it is not always possible to order the rules in this way. There exist grammars that require different orderings to achieve the longest match on different input strings. This is an illustration of the difficulty in reasoning about generalised versus standard parsing techniques.

9.3 JavaCC¶

Another tool that extends the recursive descent technique is JavaCC. The Java Compiler Compiler uses an LL(1) algorithm for LL(1) grammars and warns users when a parse table contains conflicts. It can cope with non-deterministic or ambiguous grammars by either setting a global lookahead value to a value greater than 1, or by using a lookahead construct to provide a local hint. Left recursive grammars need to have left recursion removed as is the case with ANTLR and PRECCx.

The remainder of the tools we consider are based on the standard deterministic LR parsing technique.

9.4 BtYacc¶

Backtracking Yacc is a modified version of the LALR(1) parser generator Berkeley Yacc that supports automatic backtracking and semantic disambiguation to parse non-LALR(1) grammars. It has been developed by Chris Dodd and Vadim Maslov of Siber Systems. The source code is in the public domain and available at http://www.siber.com/btyacc/.

When a BtYacc generated parser has to choose between a non-deterministic action, it remembers the current parse point and goes into trial mode. This involves parsing the input without executing semantic actions. (There are some special actions that can be used to help disambiguation and hence are executed when in trial mode but these are declared differently.) If the current parse fails, it backtracks to the most recent conflict point and parses another alternate. A trial parse succeeds when all the input has been consumed, or when an action calls the YYVALID construct. The parser then backtracks to the start of the trial parse and follows the newly discovered path executing all semantic actions. This, it is claimed, removes the need for the lexer feedback hack to find typedef names when parsing C.

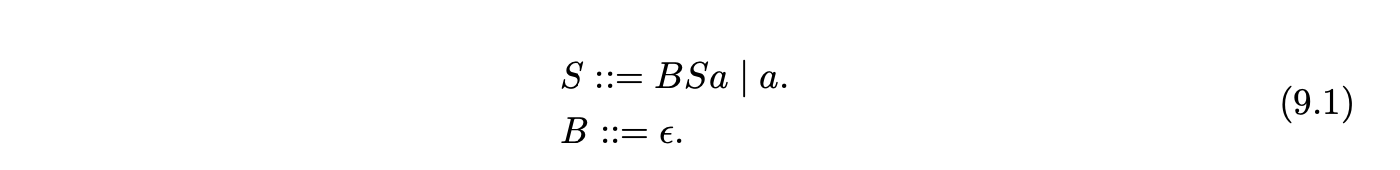

Although BtYacc does not require the use of special predicates used by toolssuch as ANTLR, its approach can lead to the incorrect rejection of valid strings if not used carefully. Furthermore, simple hidden-left recursive grammars can cause BtYacc to fail to terminate on invalid strings. For example the generated parser for Grammar 9.1 fails to terminate when parsing the invalid string \(aab\).

BtYacc extends LR parsing using backtracking. The remaining three tools we discuss are based on Tomita’s GLR approach that was designed to be more efficient than simple backtracking.

9.5 Bison¶

An indication that GLR parsing is becoming practically acceptable has come in the inclusion of a generalised parsing algorithm in the widely used parser generator Bison [2]. Although the parsing algorithm implemented is described as GLR, it does not contain any of the sophistication of Tomita’s algorithm. In particular, it does not utilise the efficient GSS data structure. Instead it constructs what Tomita describes as a tree structured stack (see Chapter 4). As a consequence of this implementation, Bison cannot be used to parse all context-free grammars. In fact, Bison fails to parse grammars containing hidden-left recursion.

For example, the inefficiency of Bison’s GLR mode prevents it from parsing strings of the form \(b^{d}\), where \(d\geq 12\), in Grammar 6.1.

9.6 Elkhound: a GLR parser generator¶

Elkhound is a GLR parser generator developed at Berkeley. It is directly based on Tomita’s approach. Elkhound focuses on the inefficiency of GLR parsers when compared to deterministic techniques such as LALR(1) and uses a hybrid parsing algorithm that chooses when to use GLR or LR on each token processed. It is claimed that this technique produces parsers that are as fast as conventional LALR(1) on deterministic input [13].

The underlying parsing algorithm described in [10] is the same as the algorithm described by Rekers. The authors attribute the slower execution time of GLR for deterministic grammars to the extra work that needs to be done during reductions. Elkhound improves the performance of its generated GLR parsers by maintaining the deterministic depth of each node in the GSS. The deterministic depth is defined to be the number of edges that can be traversed before reaching a stack node that has an out degree \(>1\).

For ambiguous grammars it provides the user with an interface that can be used to control the evaluation of semantic values in the case of an ambiguity. Deterministic parsers usually evaluate the semantics associated with a grammar during a parse. A non-deterministic parser requires more sophistication to achieve this since a parse may be ambiguous. Elkhound requires the definition of a special merge function in the grammar that defines the action to take when an ambiguity is encountered. If the ambiguity is to be retained, it is possible to yield the semantic value associated with a reduction only to later discover that the yielded value was ambiguous and hence should have been merged. An approach is presented in [14] that avoids this’merge and yield’ problem by ordering the application of reductions.

9.7 Asf+Sdf Meta-Environment¶

The Asf+Sdf Meta Environment [13] is a tool, developed at CWI, for automatically generating an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) for domain specific languages from high level specifications. The underlying parsing algorithm is Farshi’s algorithm. Asf+Sdf’s goal is to provide an environment that can minimise the cost of building such tools, encouraging a high level declarative specification as opposed to a low level operational specification. It has been used successfully to perform large scale transformations on legacy code [10]. This section presents a brief overview of the tool focusing on the parsing algorithm used.

Software renovation involves the transformation or restructuring of existing code into a new specification. Some common uses include “simple global changes in calling conventions, migrations to new language dialects, goto elimination, and control flow restructuring.” [11].

One of the problems of performing transformations of legacy code is that there is often no standard grammar for a specific language. In the case of Cobol there is a variety of dialects and many extensions such as embedded CICS, SQL and DB2. Since the deterministic parsing techniques are not compositional these extensions cannot be easily incorporated into the grammar.

Another problem is that the existing grammars of legacy languages are often ambiguous. Since ambiguities can cause multiple parse trees to be generated, the parser is required to select the correct tree.

The front end of compilers and other transformational tools are traditionally made up of a separate lexer and a parser. Certain languages, like PL(1), do not reserve keywords and as a result the lexical analysis, which is traditionally done by a lexer, using regular expressions, is not powerful enough to determine the keywords. As a result the Asf+Sdf Meta Environment uses a Scannerless GLR (SGLR) [12] parsing algorithm to exploit of the power of context-free grammars for the lexical syntax as well. The SGLR algorithm is essentially the Rekers/Farshi algorithm where the to kens are individual characters in the input string and one of the four disambiguation filters are implemented.

Asf+Sdf provides four disambiguation filters that can be used to prune trees from the generated SPPF. The primary use of the disambiguation filters in SGLR is to resolve the ambiguities arising from the integration of the lexical and context-free syntax [25]. The implementation of these filters is defined declaratively on a post-parse traversal of the SPPF. However, the parsers performance can be improved if they are incorporated into the parse.

The disambiguation filters used by SGLR are practically useful, but some ambiguities cannot be removed by them. Research is continuing on new techniques for formulating disambiguation filters alongside the parsing algorithm.

Another application that uses the same SGLR parsing algorithm for program transformations is XT [26].