3. The development of generalised parsing¶

The field of parsing has been the focus of research for over 40 years, but we still have not found the holy grail of the parsing world - a linear time general parsing algorithm. We do not even know if it is possible to parse all context-free languages in linear time. This chapter is a tour of the major developments of generalised parsing and a discussion of the links between the different algorithms.

3.1 Overview¶

There are many different parsing algorithms described in the literature. By tracing their development, valuable insights can be gained. Techniques that may at first appear to be different, can often be related. For example, the CYK algorithm [CS70, You67, KT69] is the unification of several independently developed algorithms. Furthermore, the CYK algorithm has been shown [GH76] to be equivalent to the algorithm developed by Earley [Ear68]. This opinion has been voiced before by Dick Grune [GJ90],

When we consult the extensive literature on parsing techniques, we seem to find dozens of them, yet there are only two techniques to do parsing; all the rest is technical detail and embellishment.

Many algorithms have been developed in response to limitations of, or to incorporate optimisations of, existing techniques. For example, GLR algorithms, initially described by Tomita [Tom86], are extensions of the standard LR algorithm. As we shall discuss in later chapters, Nozohoor-Farshi [NF91] removes the limitations of Tomita’s algorithm, whilst Aycock and Horspool [AH99] incorporate Tomita’s efficient data-structure to optimise a separate algorithm.

Recently, approaches that were previously deemed too inefficient are becoming practical solely due to the rapid increase of computing power. Tomita’s algorithm was developed in the context of natural language parsing where input strings are typically short. At that time, the use of his algorithm for parsing programming languages was considered infeasible. However, as we shall see in Chapter 9, several commonly used tools implement variants of Tomita’s algorithm.

This chapter presents an overview of the relationships between different generalised parsing techniques and provides two of the most straight-forward algorithms - Unger’s algorithm and the CYK algorithm.

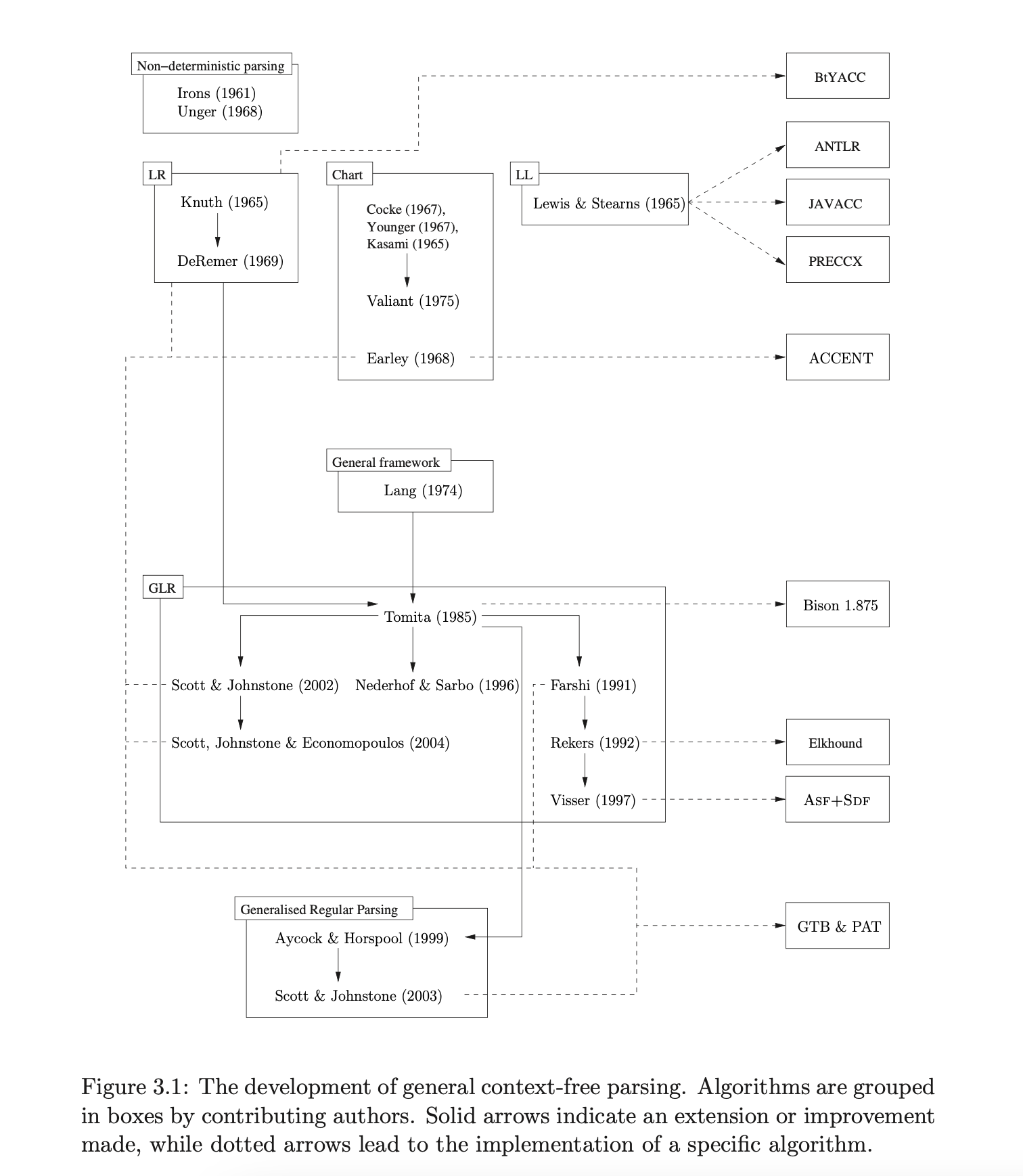

– Unger’s algorithm and the CYK algorithm. The diagram in Figure 3.1 lists several algorithms by the names of its developers, grouping similar approaches together in boxes. Solid arrows between algorithms indicate an extension or improvement made, while dotted arrows lead to the implementation of a specific algorithm.

The box on the top left of Figure 3.1 shows two early general context-free parsing algorithms. The technique described by Irons [Iro61] has been credited as being the “first fully described parser” [GJ90]. It is a full backtracking recursive-descent, left-corner parser that displays exponential worst case time complexity.

The second approach, attributed to Unger [Ung68], is a straightforward general parsing algorithm that has been “anonymously used” [GJ90] by many other algorithms. Although other algorithms, like CYK, are more efficient and have had more attention, Unger’s algorithm has been modified by Sheil to achieve the same performance [She76]. It has the advantage of being extremely easy to understand and as such we give an overview of the technique in this chapter.

The existing (general) parsing algorithms were too inefficient to be used as programming language parsers. As a consequence of this inefficiency, two approaches were developed that considered only the deterministic subclass of the context-free grammars.

The LL grammars can be used to describe the syntax of a useful class of deterministic context-free grammars which include the syntax of many programming languages. Lewis and Stearns [AU73] are considered to be major contributors to the development of the top-down LL parsing technique. Although LL parsers are efficient (linear time) they do not accept left recursive grammars. It is often useful to define programming language grammars using left recursion and whilst standard removal algorithms exist [AU73], the structure, and potentially the semantics, of the grammar are altered by the transformation. However, the technique is still popular because it is fairly straightforward to generate LL parsers by hand.

At about the same time, Knuth developed his LR parsing algorithm [Knu65], a bottom-up approach (described in Chapter 2) which achieves linear time parsing of a context-free subclass larger than the class of LL grammars. In particular, they can cope with deterministic left recursive grammars. However, the requiredFigure 3.1: The development of general context-free parsing. Algorithms are grouped in boxes by contributing authors. Solid arrows indicate an extension or improvement made, while dotted arrows lead to the implementation of a specific algorithm.

automata were too large to be of practical use. Although smaller automata were developed [1, 2], generating them by hand was a difficult and laborious task. The development of parser generators, in particular Yacc [15], made LR parsing a popular approach for programming language parsers.

Whilst the programming language community focused on improving the efficiency of a useful (restricted) class of context-free grammars, the natural language processing community required more efficient parsers for all context-free grammars. The CYK algorithm was independently developed by Cocke [10], Younger [14] and Kasami [12] in the 1960’s. The algorithm parses all context-free grammars in worst-case cubic time, but relies on grammars being in two-form. We discuss the CYK algorithm in more detail in Section 3.3 of this chapter.

Another technique developed later by Earley [1] performs better in some cases but has a similar worst case complexity to CYK. Earley’s approach is a directional, bottom-up technique. In this respect it appears to be very different to CYK, but it has been shown [13] that the two algorithms are in fact closely related. We discuss Earley’s algorithm in more detail in Chapter 8.

Many programming language developers were content with efficiently parsing a subset of the context-free grammars and new programming languages were designed with grammars that were ‘easy’ to parse. It was not until the 1980’s that an interest in generalised parsing resurfaced in the form of Tomita’s GLR parser [15]. Tomita’s algorithm extends the standard LR parsing technique to parse a larger class of grammars. Although his algorithm fails to terminate for certain grammars, it parses all LR grammars in linear time. Corrected versions of Tomita’s algorithm have been given by Farshi [12], Scott & Johnstone [13] and Nederhof & Sarbo [14]. We discuss these approaches in Chapters 4, 5 and 8 respectively.

There have been many attempts to speed up the performance of GLR parsers. A novel technique presented by Aycock and Horspool improves the efficiency through the reduction of stack activity [1]. Unfortunately their technique fails to work for certain grammars. However, an extension of their approach has been given by Scott and Johnstone [13] which successfully parses all context-free grammars. We discuss these algorithms in Chapter 7.

In the remainder of this chapter we shall outline two important developments in the history of parsing. They have no immediate impact on the GLR-style algorithms that are the main topic of this thesis and we shall not need them later. However, we include them for completeness.

3.2 Unger’s method¶

One of the earliest and most straightforward general parsing algorithms is the technique developed by Unger [10]. It has the advantage of being extremely easy to understand and as such we present an example parse in detail.

Example - recognition using Unger’s method

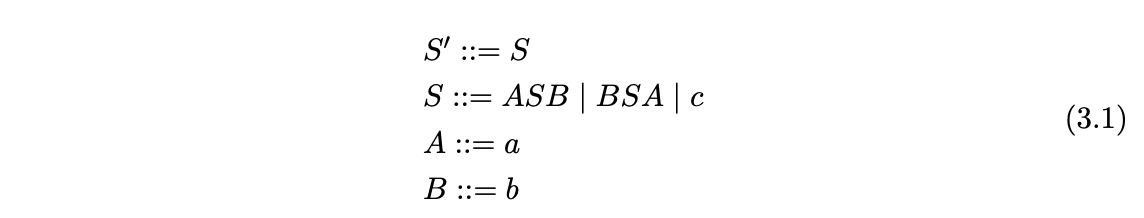

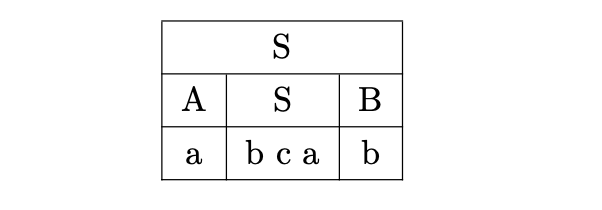

Unger’s method works by trying to partition the input string so that it can be derived from the start rule. For example consider Grammar 3.1.

We start off by partitioning the input string for the right hand side of the start symbol.

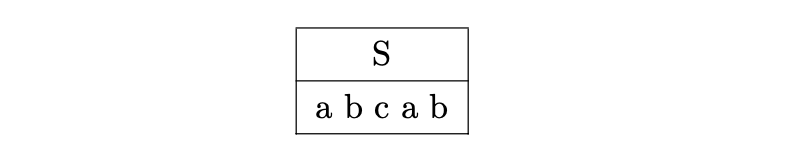

The non-terminal \(S\) can be replaced by one of 3 alternates. We start off with the first alternate and partition the input as follows.

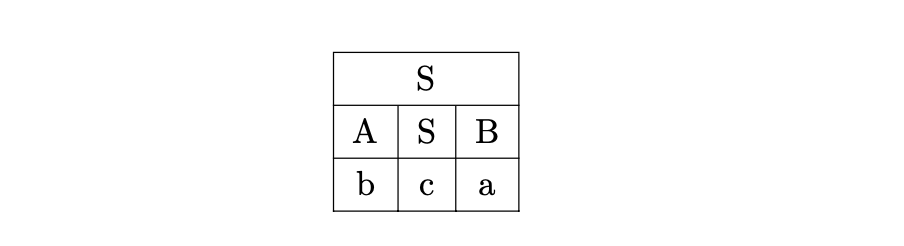

This method of partitioning can easily get out of hand if the right hand side of rules and the input string are large. Unger provided some optimisations that limited the number of partitions that need to be kept. Any partitions that do not match the terminals in the input string can be removed. This leaves us with only one partition that can possibly lead to a derivation of the input string. For example, since the non-terminals A and B cannot be extended any further, we focus on the non-terminal S, which has three alternates that can potentially be used to derive \(bca\).

Trying the first alternate we see that it cannot be used because the non-terminals A and B do not derive the terminal they have been partitioned with.

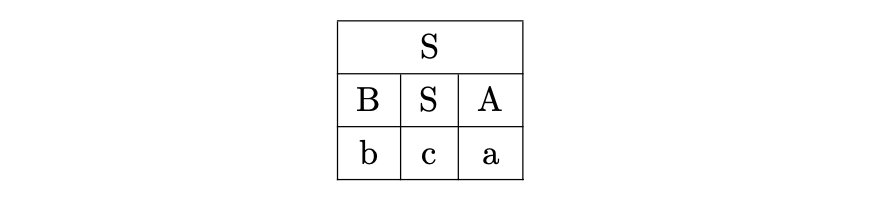

Trying the next alternate, we have a success as all the non-terminals are able to derive the terminals in one step.

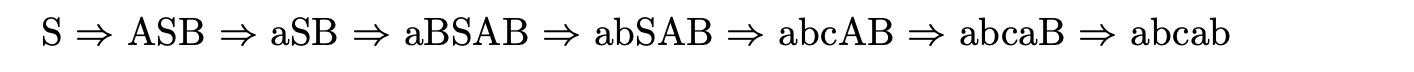

This leads us to the following (unique) derivation of the input string.

A na ̈ıve implementation of Unger’s algorithm has exponential time complexity, which limits its use to trivial examples. The addition of a well-formed substring table dramatically improves the efficiency, the complexity becomes \(O(n^{k+1})\) where \(n\) is the length of the input string and \(k\) is the maximum length of a rule’s right hand side (see [1] for more details).

The CYK algorithm¶

The CYK algorithm is a general recognition algorithm with \(O(n^{3})\) worst case time complexity for all context-free grammars in Chomsky Normal Form (CNF). A context-free grammar is said to be in CNF if every rule is of the form \(A::=BC\), or \(A::=a\), or \(S::=\epsilon\), where \(ABC\) are non-terminals and \(S\) is the grammar’s start symbol.

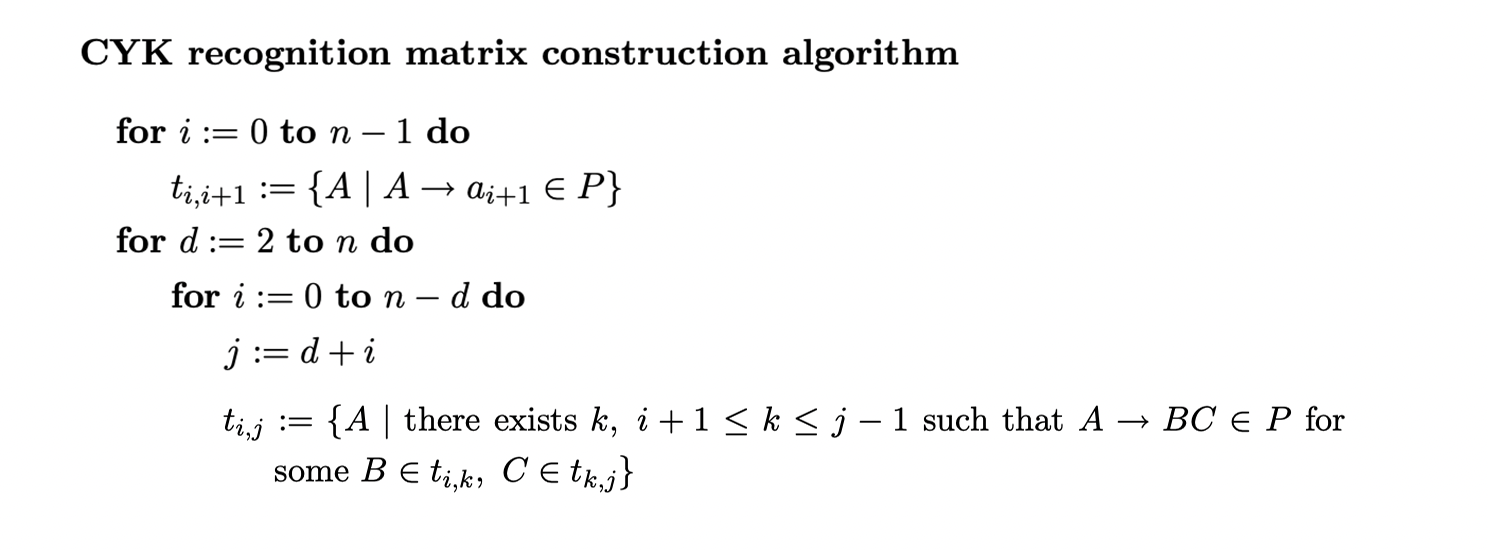

The CYK algorithm uses an \((n+1)(n+1)\) triangular matrix, where \(n\) is the length of the input string, to determine whether a string is in the language. Each cell contains a set of non-terminals that are used in a derivation. In [1] the matrix is constructed in the top right diagonal instead of the top left as is done by Cocke, Younger and Kasami. Both algorithms are equivalent, but Graham’s description is easier to compare against other chart parsers, like Earley’s algorithm. The formal specification of the recognition matrix construction algorithm, taken from [1], is as follows.

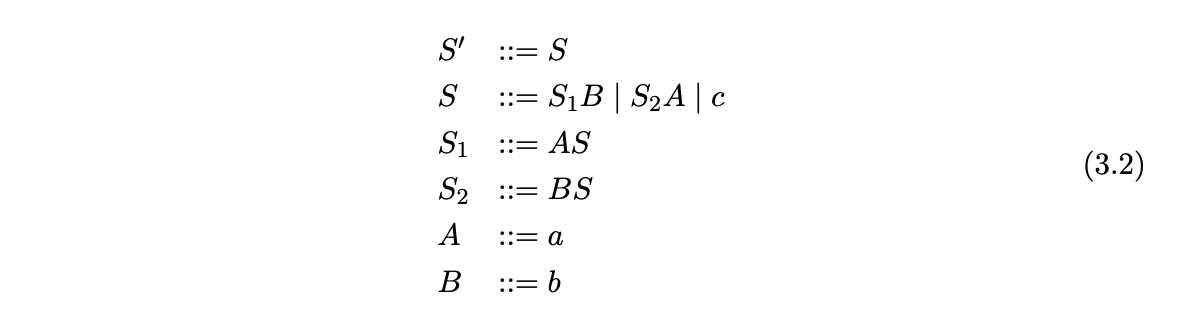

To demonstrate the recognition of a string using the CYK algorithm we trace the construction process of the recognition matrix for the string \(abcab\) in Grammar 3.1. Since the CYK algorithm requires grammars to be in CNF we use the CNF conversion algorithm presented in [1] to transform Grammar 3.1 to Grammar 3.2.

To demonstrate the recognition of a string using the CYK algorithm we trace the construction process of the recognition matrix for the string \(abcab\) in Grammar 3.1. Since the CYK algorithm requires grammars to be in CNF we use the CNF conversion algorithm presented in [1] to transform Grammar 3.1 to Grammar 3.2.

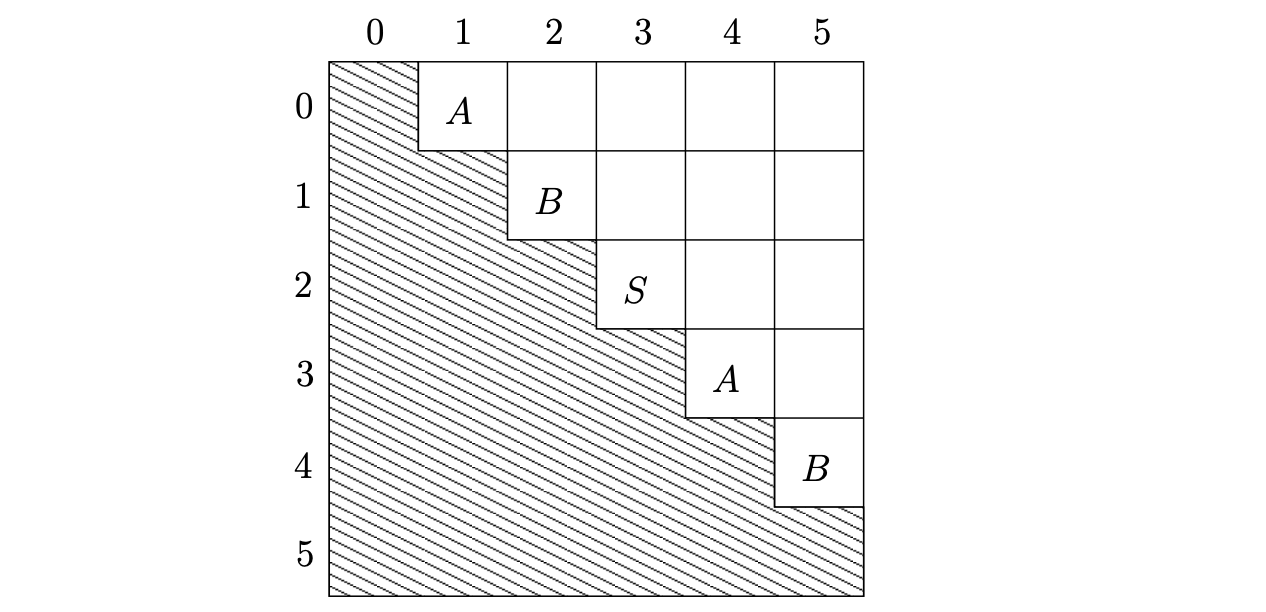

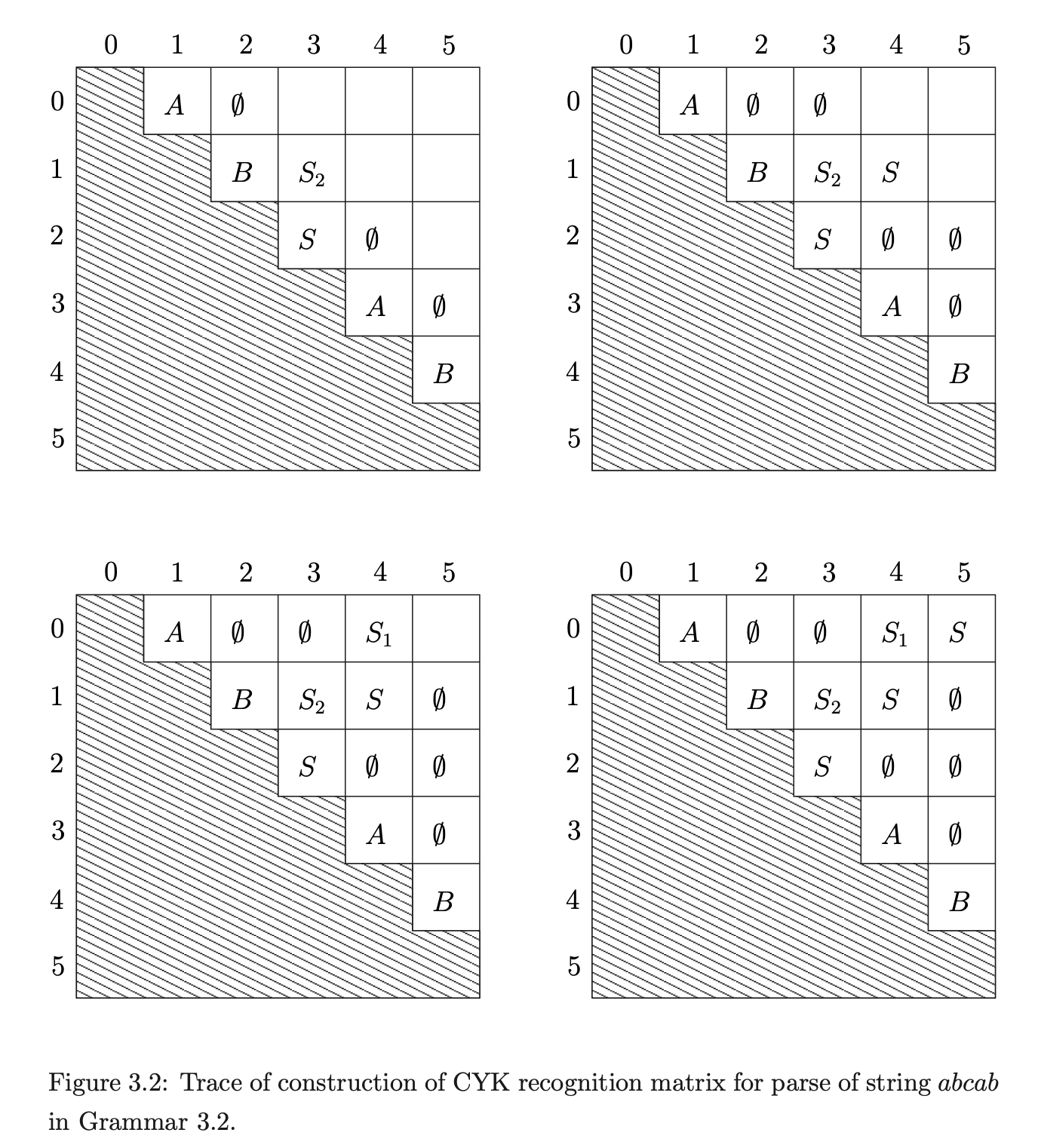

We begin the parse of the string \(abcab\) by filling the superdiagonal stripe[1] of the matrix from the top left to the bottom right of the matrix with non-terminals that directly derive the consecutive symbols of the input string.

Once the construction of the recognition matrix is complete, we check the entry in the top right cell. If it contains the non-terminal on the right hand side of the start rule then the string is accepted. In our example parse we can see that the string \(abcab\) is in the language of Grammar 3.2.

Once the construction of the recognition matrix is complete, we check the entry in the top right cell. If it contains the non-terminal on the right hand side of the start rule then the string is accepted. In our example parse we can see that the string \(abcab\) is in the language of Grammar 3.2.

3.4 Summary¶

In this chapter we have discussed some of the major developments of generalised parsing techniques. We also briefly discussed Unger’s approach and the \(CYK\) recognition algorithm.

In the next chapter we discuss, in detail, Tomita’s \(GLR\) parsing algorithm and the extensions due to Farshi and Rekers.